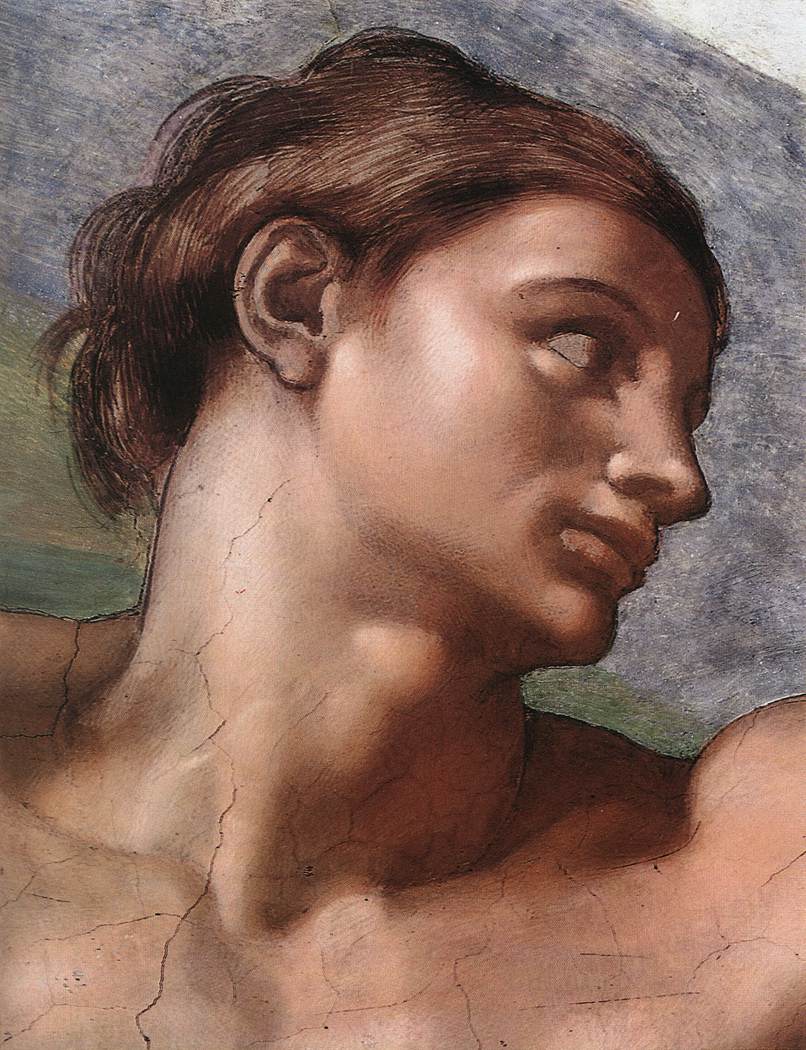

I will soon get to witness the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. As overwhelmed as I’ll be with Michelangelo’s feat, what will stand out the most for me is the way he brings everything to life – animation’s exact definition. Even looking at powerpoint slides of the different panels, it’s easy to see the various expressions, positions and sheer monumentality of every story depicted. For instance, in the Creation of Adam: God, accompanied by wingless angels and Eve under his arm, flies towards Adam who is looking lovingly at his creator. God has his finger extended to give Adam life and to establish a connection between man and God. Adam represents divine perfection which Michelangelo depicted spot on -- I gaped immediately at how beautiful this man is. It's true.

Working down the ceiling, it’s evident Michelangelo’s style began to evolve. The first panel he did was Noah’s Ark, which included the most details, the smallest figures and was much more technical than his later, much more freely painted panels with larger figures. In this painting, his experience in sculpture is seen cause the figures are grouped as such; he also stresses human drama more than movement. In later panels like Creation of Sun, Moon, Plants, there’s less detail but a lot more motion. This one almost resembles two separate frames of an animation where God is creating and then flying away later. Just like in the Expulsion of Adam and Eve, there's a great sense of storytelling because you see the same people at different times.

My favourite is possibly the Separation of Light and Darkness. With more abstract and loose brush strokes, he infuses a certain spirit in God. Anyone who sees this, almost on instinct, will start imagining God twisting his mighty body.

Mannerism, an Italian art movement in the 16th century, was strongly influenced by Michelangelo’s later work especially his incredible use of ‘contra posto’, bright colours and individualism. While looking at Pontormo’s The Deposition of the Cross, the teacher mentioned how in Mannerism, artists were beginning to find their own styles. Instead of replicating or imitating reality, they embrace a more expressive, exaggerated expression of reality -- using much looser, larger strokes and not necessarily being completely technical. I find this more interesting because I love it when an artist takes a “less is more” approach and exhibit a unique style. This idea can be drawn from Michelangelo’s later sculptural works as well. Although he never finished them, he left them ragged and roughly crosshatched with his tooth chisel, incorporating the medium’s texture. Such as the unfinished Captive. I find them much more expressive and full of life this way. Perhaps this is how he intended them.

A sculpture that captivated me which uses this same rough, expressive look is Apennine, Carved by Giambologna from real rock. The jagged texture of the rock was left on the figure working harmoniously to depict his agony.

In traditional animation, like Mannerism, style, a real sense of movement and facial expressions are exaggerated and details aren’t everything. When going frame by frame through great animated action scenes, the minutiae are often left out and the drawings might even look like a jumbled, disproportionate, gooey mess. But our eyes and mind work together to make sense of what’s happening during the short amount of time that passes. Cooooooool....

I enjoyed your analysis and appreciated the reference links. I love the comparisons to animation. Great work!

ReplyDelete